When interacting with horses and horse people, we may encounter many different phrases of jargon, which may be confusing or misunderstood even by experienced equestrians. In the Terminology Demystified series, we will explore different terms and their meanings.

The term; On the Forehand (OTF), relates to the amount of weight a horse is carrying on its front end, vs its hind end. Philippe Karl has some intricate and thorough explanations of how a horse carries weight in his book: Twisted Truths of Modern Dressage. He explains that with a rider on the horse’s back, the horse at halt typically carries 2/3 of its weight on the forelegs and 1/3 of its weight on the hind legs. The general consensus is that horses naturally carry 70-80% of their weight on their front end and 20-30% on their hind end. When a horse is on the forehand, it means that they are carrying more weight in front than they are in the back. Anatomically, the horse not only has its rib cage, neck and very heavy head resting over its front legs, but also has a rider to carry under saddle. This means that if a horse is not exercised in a way that lifts the thorax and transfers weight to its hind end, the ratio becomes severely uneven and the horse is said to be on the forehand.

So what is the big deal? If they are naturally carrying more weight on the forehand, then why would it be an issue while we ride? The answer is simple. If we want our horses to lead sound, healthy lives, working on the forehand is not an option. Working on the forehand not only leads to increased concussion and wear on the front legs, but it also hinders muscle development, minimises the amount of weight a horse can carry, and literally drops the thorax down from the shoulders and withers, possibly leading to restricted breathing, pinched nerves and an inability to remain balanced and supple.

It is important to note that just because a horse curls its neck around while it is working, it doesn’t mean that the horse is off the forehand. In fact, the placement of the horse’s head has much less to do with working on the forehand than we are often lead to believe. An overbent horse can still drop its back and be on the forehand. A horse “perfectly on or slightly in front of the vertical” can still be on the forehand. It takes training of the eyes and body to see and feel the difference between a horse on the forehand and a horse carrying its back correctly.

The above image illustrates a few key elements to look for in a horse on the forehand. The horse appears to be leaning into the contact for support, rather than carrying her own weight, as well as that of the rider. She appears to be “falling forward” into each stride, instead of being propelled forward by her hind legs. She shows a clear lateral imbalance whereby she appears to be leaning into the turn, much like a rider on a motorcycle would around a turn. If we observe each pastern on the ground, one can see that the front pastern appears to be taking more weight and strain than the hind pastern. This also means that the hind leg will leave and touch the ground a fraction of a second later than the front leg. Her tail is held tensely to the inside of the circle in order to assist with her balance. A soft, flowing tail would be an indication of better balance. Her under neck muscles appear tense as she uses her head to try to “lift” weight off her front end. Lastly, if you observe the image with soft eyes and take the entire picture into account, it appears that the horse’s barrel (ribcage, thorax) has dropped below the height of her withers. It almost seems like she is sticking her tummy out towards the ground.

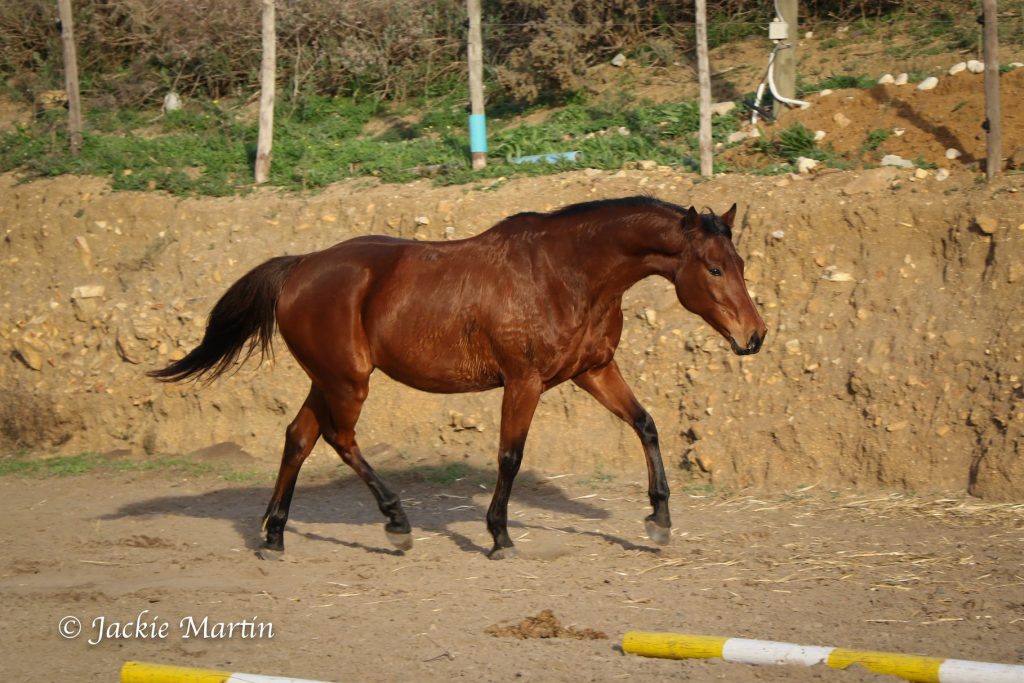

The above image is another example of the horse on the forehand, but with the other diagonal pair of legs on the ground. Note how there appears to be a dip behind the saddle and towards the horse’s croup. One symptom of horses constantly working on the forehand is this loin area being under-muscled, weak and tense. This is the only area along a horse’s spine that is not supported by ribs, so general back weakness will show up here and directly behind the withers and shoulder blades.

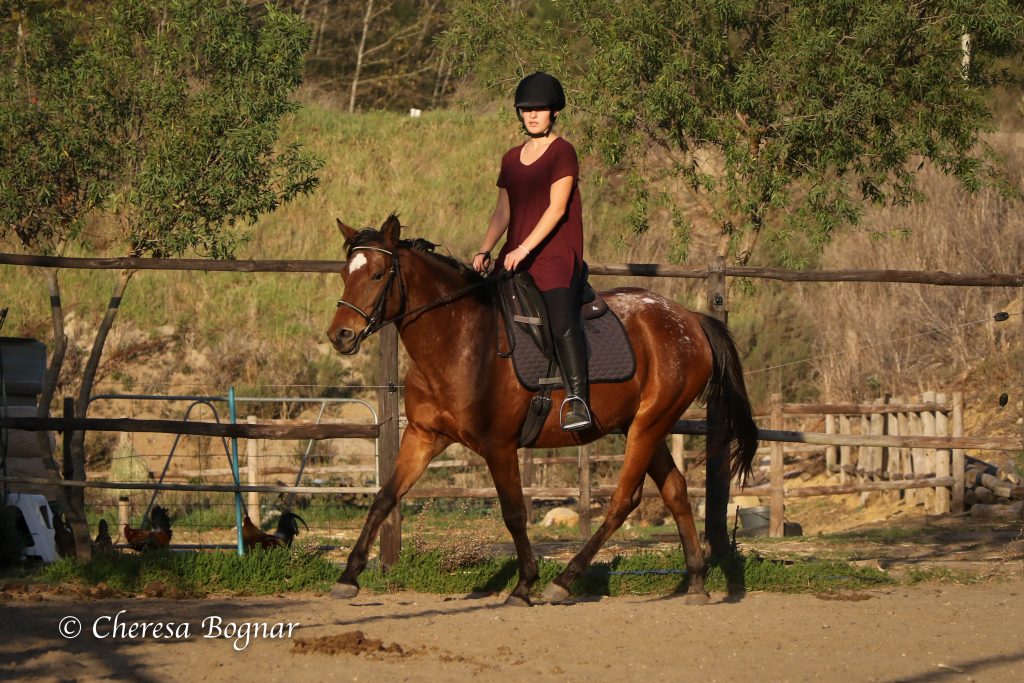

In the above photo, the same horse is starting to show elements of lightness. Although she is still on the forehand, there is an improvement from the previous images, namely, her underneck muscles are relaxed, she is able to propel her neck more forwards and out without losing balance, her loin area is no longer dropped and her stomach muscles appear to be working in order to lift her thorax underneath the rider. Her tail, although still needed for balance, is starting to lift and swing more.

Here, she is further showing self-balance. Although she is travelling on a downhill section of the arena (shown by the rider leaning back further than we would like), she appears to have a relaxed under neck, her tail is swinging and she is actively trying to lift the rider’s weight by lifting her own ribcage upwards.

Below are some examples of a horse who is not on the forehand. The rib cage appears very full and lifted, almost as if it is a balloon about to float up and away. The withers appear higher than the croup. The hind legs are actively reaching not only forwards underneath the bulky weight of the barrel, but also upwards, giving the appearance of springiness and power.

You will notice that the horse’s head position changes in each photo, but the elements of a lifted wither and active hind end remain unchanged. Of course elements of each photo still show heaviness on the forehand, but the overall picture is that of “floatiness” and power.

When we are viewing horses at work or in the field, it is good to train to see whether a horse is working more with its front end than its hind end. It is also key to remember that fast does not equal light. Chasing a horse forwards with the goal of achieving an active hind end, without ensuring that the horse is light and balanced in front, will only compound the issue of the horse travelling on the forehand. Look for issues such as struggling with saddle fit, a dip behind the withers and shoulder blades, an angular or “jointy” appearance of the spinal process in the loin area, a dip between the sacrum and spine, under-developed hindquarters, a very round belly appearing to drop towards the ground, a flat, saddle-like indentation where the saddle sits on the horse’s back, ongoing issues with chipped or weak front hooves and issues with front shoes being lost. Joint issues will often also appear in the front legs and injury may be frequent.